Sej Saraiya

@sejsaraiya

Photographer based in the US

From a very young age, photography shaped the way I saw the world. My camera was both an excuse and an instrument for me to stop for a moment in time and fully engage with my surroundings, something that continues to hold true even today when I travel. I learned to see the world from a deeper perspective from behind my lens. Landscape photography taught me patience and appreciation for the only heritage we have—our planet Earth.

"And observing indigenous people from behind my lens gave me the opportunity to be non-judgmental and non-imposing, to instead observe and learn."

My search for indigenous communities started initially as a means of self exploration. I was at a lecture by Canadian ethnographer Wade Davis—whose work has since been a big influence on my life—where he talked about remote cultures living in a way that was alien to us in the modern world. But every story he shared about them sounded more and more familiar to my own way of thinking, and I realized I wanted to spend some time with these people and experience it first hand.

"So I gave up my life in Los Angeles and took off on a years-long journey to meet these cultures and explore their ways of living, being, and interacting with the Earth."

Learning about co-existing with bears and wolves; observing first hand how death truly is a part of life; viewing in action agricultural practices without the use of machinery or pesticides among a tribe living remotely in the mountains, it was all so mind-expanding, that there was no going back. The knowledge and life philosophies discussed by each tribe only grew more and more fascinating. Once I started to spend time with them—observing them and learning from them—the obvious next step was to take portraits of their lives and their surroundings.

"The photographs were thus a by-product of my journey."

When I started off, I didn’t really know how to connect with them yet; I didn’t know if it was the right thing to give them money if they asked for it, or what I could talk to them about and what I couldn’t. There was this invisible boundary within my heart from a sense of unfamiliarity with people I knew nothing about, many of whom lived in poverty, or so I perceived. Reminding myself that I was simply here to learn from them (and not to take something away nor give them something I thought they needed) became my doorway into their intimate lives.

Often, I’d hand my camera over to a curious child and let him or her take some photographs, not as an act of charity but simply because I was curious to know what they thought was interesting about their own people. Sometimes, especially if I needed help carrying something, I’d ask one of the village kids to be my “assistant” and let them set up the tripod for me. I always showed them the photographs on my camera screen after the fact.

"They enjoyed knowing about the process. It created a sense of oneness between us."

Additionally, being a woman traveling alone naturally gave me a place within the communities of women wherever I went. They took me in and protected me. Also, spending so much time with indigenous women was a complete blessing. To be on their land and live their life is like traveling back in time. To be able to learn the old ways of women and observe how they show up for each other and even a stranger like myself was revitalizing. Watching the women of the desert walking barefoot with pots of water balanced on their heads in the sweltering heat of the Indian desert, to come home and cook for their families while staying veiled; their strength as they collected wood, and basically ran the family showed me the power of these women who did it all without losing their softness, their femininity.

Sometimes, if I knew I was visiting a village with a strictly meat-based diet (I’m vegetarian), I’d take my own lentils and cook khichari (lentil soup) for the tribe, introducing them to my own native food. It was always an exchange of some sort, and almost never involved money. But did involve a lot of stories, photos, foods, jokes, etc. It was all about dissolving the boundaries between myself and a group of people that seemed so unfamiliar but were truly not.

Outsiders, in the lives of remote cultures, have mostly been missionaries who have taken from them all that was familiar to them to force them to convert into their ways, which has done good no doubt, especially in ending traditions that weren’t serving the people (like the violent practice of headhunting), but has also caused just as much harm. And so there’s a natural apprehensiveness about outsiders among the remote cultures. They have a strong insider-outsider dynamic and rightly so. It helps them keep away those who might cause harm, and protect their age-old oral traditions which are so precious to them.

"Additionally, among many indigenous traditions is a belief that the camera will steal their soul, and as ludicrous as it may sound, they’re not totally wrong."

Every now and then tourists barge into the lives of these people and sneak photographs without any interaction with them nor exhibiting curiosity about their culture. This trend in contemporary times which entails taking photos only with the intention of sharing them often distracts people from truly engaging with their surroundings. Furthermore, it dehumanizes indigenous people turning them into objects of fascination. No mention is made of their stories, their lives, their culture.

In that light, I have been refused a photograph or two particularly during my initial months of travel when I didn’t know yet how to interact with them. But that changed over time. As I started to spend more time with the tribes I visited subsequently, I was almost never refused a photograph or stories.

"I almost always travel alone, and when you do that, they’re more receptive of you."

As I mentioned before, I’ve been taken in, protected, my needs met. In return, I have been “forced” to wear their tribal attire and join the entire tribe in their prayer dance for the Earth. I have been asked to pose for photographs with the entire village. Attend weddings and funerals, visit their deceased, or watch Fast and the Furious 3 in their local language on their small TV with the entire family (of 8 girls). I have been taken in by indigenous women and forced to stay at their homes until I was “fit“ (fat enough) to travel again.

Every photograph I’ve ever taken of tribe members has been with utmost reverence that comes from deep within me. I have an indelible respect for these people who live off the land they’re born in and exhibit so much respect for the living landscape. The wrinkles on their faces carry innumerable stories, the art on their bodies carry symbolisms and historical significance, their interaction with their surroundings is sacred and humbling.

The Eastern world is a spiritually charged ethnosphere, where a persistent awareness of unity and mutual interrelation of all things and events is ingrained in daily rituals.

"Through photos and film, I hope to share with the viewer the naked, rampant, symbiotic non-duality (oneness) in our chaotic world."

For example, my short film “The Language They Spoke” is an ode to silence. A good deal of contemporary society has an unhealthy relationship with silence. People fear silence and often rush to fill the space with meaningless substances so that they are no longer uncomfortable. In the East, silence is an essential part of existence. Eastern traditions highly revere silence as the Language of Gods, the living force leading to the peaceful unmoving state of self. In a world which is constantly feeding us information, silence becomes crucial. This poetic silent film invites the viewer to not only reconnoiter their unease if any, but also question it and ultimately find repose in this instrument of discomfort.

"Spending time with indigenous people inherently becomes a spiritual journey."

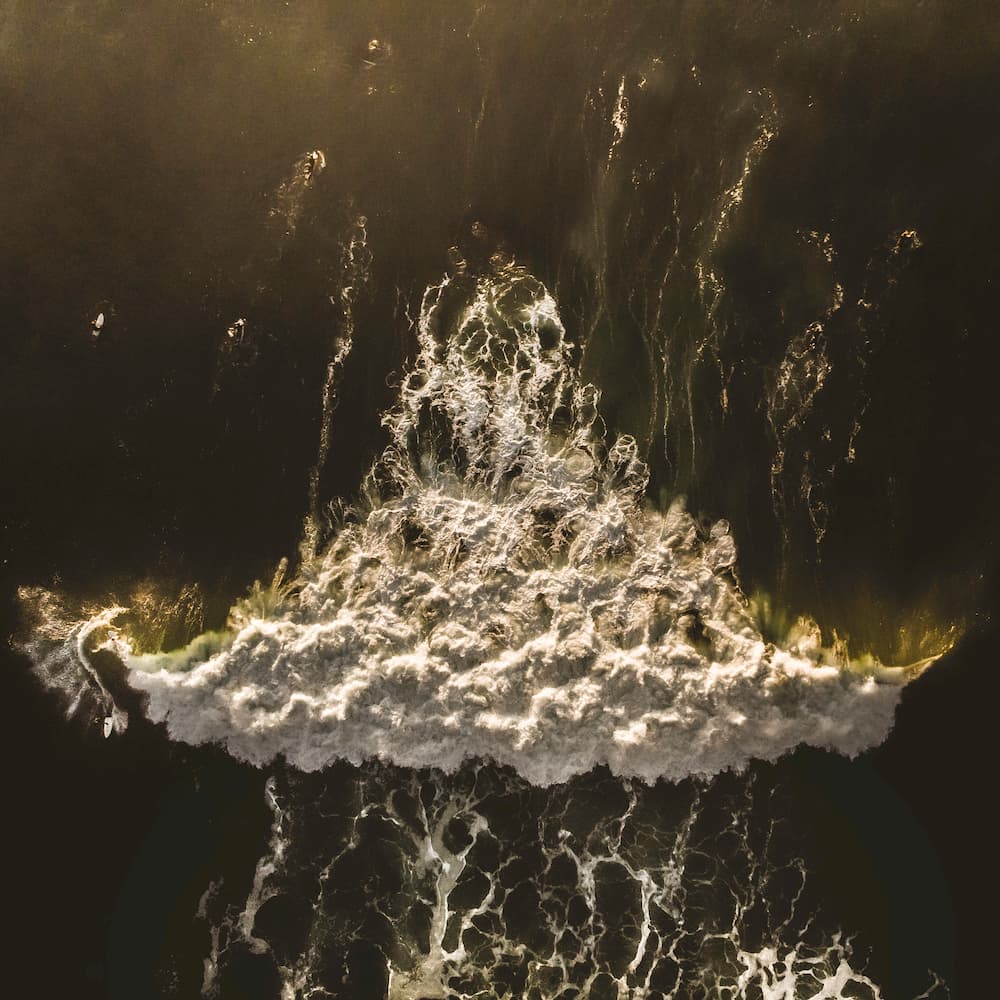

They have so much knowledge and wisdom that comes from centuries-old traditions passed down orally. My exposure to their ways of thinking shifted my senses and changed the way I looked at the world. It even changed the way I took photographs of the landscapes around me. Among the indigenous, every sound is a voice, every mountain is being, every encounter a meaning. What simply used to be majestic mountains or oceans or beautiful river valleys turned into teachers of life and precious heritage rich with ancient wisdom and stories from the human past.

"A big portion of my landscape photography is now informed by what I have learned from them."

Every photograph I have ever taken was with the intention of provoking a discussion. Every face I’ve ever captured carries stories worth lifetimes of a whole tribe. Wade Davis, during a lecture said that, “Indigenous cultures are not failed attempts at modernity, let alone failed attempts to be us. The world in which you were born is just one model of reality.” This information has since lodged itself deep within me. Many of us in the modern world continue to look at remote cultures through eyes of pity, escorting the belief that we need to help them change their ways and become more like us.

"But the reality is that they don’t need us in the way we think they need us. And with most certainty, we need them."

A lot of the life philosophies that are being taught in new age spiritual books, these tribes actually live them. I hope to remind people of their roots through my exhibitions and lectures—something that modern life pushes us toward forgetting. I also want to stimulate youth to get behind the lens and document the world through their eyes not only to bring something back, but also to help them slow down and take a good look at the world they’re growing up in.

"When you’re behind the lens, you learn to see things from a deeper perspective."

That is one of the major reasons why I sell my prints. To have photographs of remote cultures hanging on the walls of people around the world helps invoke curiosity about a culture completely different from one’s own and start a conversation that could potentially help expand one’s mind beyond what we already know, and help find solutions to the environmentally unfeasible lifestyles we have adopted. As long as their stories are not shared, they remain objects of fascination. Sharing stories about them not only humanizes them but also reminds us that there are other ways of being, apart from the one model of reality we are used to.

"My time and experiences with remote cultures have been very humbling and continue to be so."

Through observing them, I learned to become more connected with the living world around me. It’s important to remember that they practice traditions that have been passed down orally through generations, ones that work in harmony with the world around them. Their relation to their living landscape is balanced and reciprocal, never taking more from the living land than they return to it, and they are continually engaged with it.

"Even the size of a hunt is negotiated between the community and its surrounding."

There’s one story in particular that beautifully shows this and impacted me greatly. I was in a small town in northern British Columbia, right by Alaska with a group teaching an Indigenous Filmmakers’ Masterclass, where I met a medicine woman. While telling me about the plants endemic to the region, she pointed out to a mountain far away from us saying she was going, by foot, to that forest the next evening to pick some herbs, if I wanted to go with her. I asked if we could go in the morning instead because I had a flight back later that day, and she looked at me appalled. In the morning the bears and the wolves went berry picking, she said to me.

"The forest was theirs. In the evening, when they were done and resting, the forest was ours."

I have shared this story countless times because it was a pivotal moment in my life. In spite of having grown up vegetarian for the love of animals, and having grown up around cows and goats, feeding cats and crows, I had never thought of “sharing the forest” with other animals or knowing about their routines. I grew up in a city, and in cities we are often so disconnected from other living beings except for our pets and house-plants that we bring home to energize our homes. For us. I realized that all other living beings which surround us, within as well as out of sight, have a routine of their own, and that we’re all sharing this planet earth. We might want to stop for a second and think about them as well.

We’re simply here as visitors. Let us remember to respect that and maintain humility and gratitude while traversing the world. Photography and film have allowed me to experience so many distinct lives, cultures and arts in one lifetime. Through my camera, I have learned about various different worlds. And through the connections, I have learned we are, still, all one.

Would you like content like this sent to your inbox?

MUST READ STORIES OF OCTOBER

MUST READ STORIES OF SEPTEMBER

MUST READ STORIES OF AUGUST

MUST READ STORIES OF JULY

MUST READ STORIES OF JUNE

MUST READ STORIES OF MAY

NOMADICT

ART GALLERY

THE LATEST STORIES

WRITEN WITH PASSION TO INSPIRE YOU

A guide to Toruń, Poland: A golden hour haven for telephoto tales in crimson and gold

Toruń, set along the Vistula River in north-central Poland, is a UNESCO-listed gem where Gothic brick façades glow in the last light of day. Small and unhurried, it’s a city made for slow wandering, and for watching golden hour turn terracotta rooftops into crimson and gold.

Kasper Rajasuo (@rajasuokasper): Best of the Week 46 at #nomadict

From childhood hikes to award-winning shots, Kasper Rajasuo’s journey is one of rapid evolution and deep connection. In this article, Kasper shares the technical secrets behind his “Santa’s Cabin” winning photo, the four lessons that defined his career, and how he uses color theory to transform harsh Finnish winters into dreamy, serene masterpieces.

Andy Rider (@andyswildlife): Best of the Week 2 at #nomadict

Andy Rider is a passionate wildlife photographer and filmmaker based in South Africa, dedicated to capturing the raw beauty of nature while raising awareness about conservation. Inspired by legends like Steve Irwin, his journey began as a field guide, where he honed his skills and developed a deep respect for ethical wildlife photography.

Philipp Pilz (@buchstabenhausen): Best of the Week 43 at #nomadict

In this article, photographer Philipp shares how time, clarity, and consistency have shaped his evolving relationship with nature photography. Drawn ever further north, he writes about embracing uncertainty, working with restraint, and finding beauty even when plans fall apart — including the unlikely story behind his Best of the Week–winning image.

Tom Fähndrich (@tofenpics): Best of the Week 47 at #nomadict

Tom shares the journey behind his winning photography, from a passion for exploration and remote places to field lessons, composition choices, and color grading.

Photo tour in the Faroe Islands

Join us in the Faroe Islands for a unique photo tour, where you’ll elevate your creative skills with expert guidance from Ronald Soethje and Nomadict.

Photo tour in Azores, Portugal

Join us in the Azores for a unique photo tour, where you’ll elevate your creative skills with expert guidance from Ronald Soethje, Bruno Ázera, and Nomadict.

Forest Kai (@forest1kai): Photographer based in the US

In this article, Forest shares how years of chasing scale, silence, and raw landscapes shaped his approach to photography, from the deserts of Kazakhstan to the volcanic ridges of Iceland. He talks about how he uses light, texture, and vast negative space to create images that feel both intimate and overwhelming.